When the Wallet Empties

Thin seasons and the wider vocabulary of provision

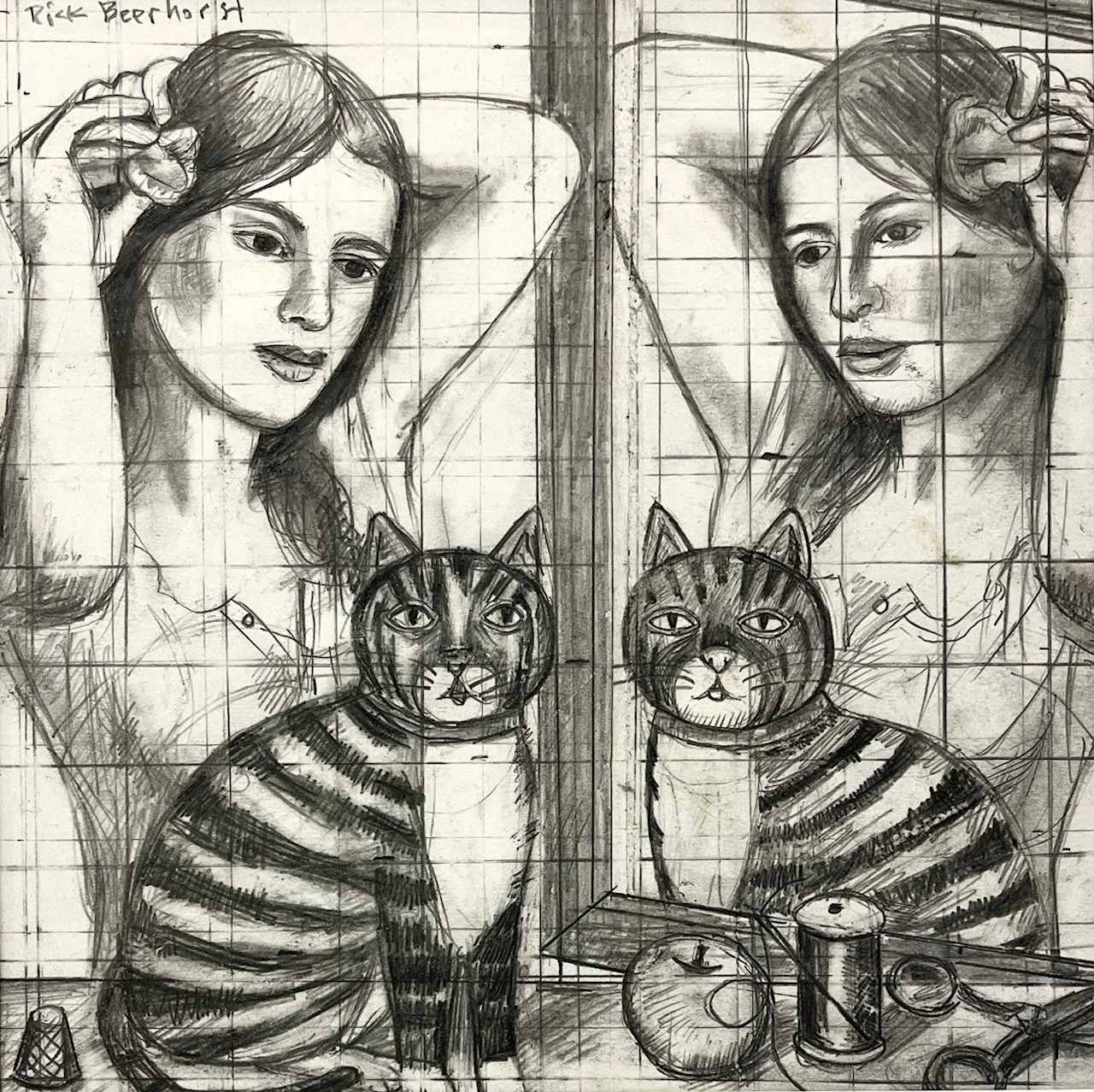

M working in the studio that came along with my ‘free’ stay in Bavaria for the whole summer.

There is a spell on the modern mind.

It repeats one line:

If you just had more money, everything would relax.

Money is useful. I enjoy a flush account. It buys time and removes friction.

But it is a narrow pipe to force all provision through.

We have trained ourselves to believe currency is the only delivery system life is allowed to use. As if existence were a vending machine and the only acceptable coin were cash. Insert card. Select comfort.

So people harness themselves to work they tolerate or quietly resent because they cannot imagine another configuration. The imagination has thinned. It scrolls. It binges. It dulls.

Meanwhile something older waits.

I have been self-employed my entire adult life. I have raised six children on unpredictable income. I have lived under a silver maple on Fuller Avenue in Grand Rapids with boxes of clothes appearing anonymously on our porch. My kids tore into them like treasure chests. No invoice. Just circulation.

In Bavaria, an 80-year-old woman running an Airbnb insisted I stay for free after a year of shared meals and long conversations. The first year I paid. The second year I was a guest.

I have watched this pattern repeat for decades.

When the wallet empties, other channels appear.

Rooms open.

Meals arrive.

Friendships turn into shelter.

Not fantasy. Not irresponsibility. Pattern.

I am not romanticizing scarcity. I prefer a healthy bank balance. But I have learned that money is only one language of provision.

When the numbers shrink, the senses sharpen.

Boredom without a screen becomes ignition.

Loneliness becomes a corridor.

Silence becomes a workshop.

In those stripped-down seasons, resourcefulness wakes up. Relational intelligence deepens. You begin to see how much of life flows outside the marketplace.

Most people never stay long enough to discover this. They anesthetize the discomfort. Scroll. Stream. Sedate.

But if you stay, if you let the thinness do its work, something expands.

You begin to live inside story again instead of subscription.

You begin to experience provision that does not show up on a spreadsheet.

Money is cool. Earn it. Steward it.

Just don’t reduce your imagination to it.

Provision has a wider vocabulary than currency.

And the empty-wallet season might not be a failure state.

It might be the doorway.

A creative life throws things away because it trusts continuity

Every morning beginning somewhere between 5:00 and 6:00 a.m. I sit down with a Bic pen and a blank notebook from the grocery store and write.

I don’t hesitate.

I don’t warm up.

I don’t try to sound intelligent, insightful, or worth saving.

I just write.

Much of what comes out is repetitive. The same thoughts circling. The same questions knocking on the same door. If I were to reread it later, most of it would be boring, even to me. That’s not a flaw. That’s the function.

That hour isn’t for producing anything.

It’s for clearing something.

I’m not composing essays. I’m letting the mind run out of its rehearsed material. I’m loosening sediment. Meaning doesn’t arrive as brilliance. It arrives after insistence burns itself out.

When the notebook is full, I throw it away.

No archiving.

No rereading.

No saving it “just in case.”

People are often shocked by this. They imagine waste or loss. For me it feels like completion. The notebook was never an artifact. It was a vessel. Once it’s done its work, keeping it would only harden what was meant to move.

That act of discarding is what makes the writing honest. The moment a future reader enters the room, the body tightens. But when I know the pages will be recycled, the pen moves freely. Nothing has to prove itself. Nothing has to survive.

And something essential always does.

Out of that unremarkable, disposable hour come the essays that later feel precise. The handwritten letters that land with warmth. The small, exact comments that say what needs to be said. The conversations that leave people lighter when I walk out the door.

The value was never on the page.

It was in what was dislodged.

There’s a line in the Psalms that reads, “Teach us to number our days, that we may gain a heart of wisdom.”

Not fear our days.

Not rush them.

Number them.

Countability, not anxiety.

And in Ecclesiastes there’s that unsentimental inventory of decline: the silver cord snapping, the golden bowl breaking, the wheel at the well finally giving way. It isn’t moralistic. It’s mechanical. The body is named for what it is: a finely tuned, temporary instrument. When it breaks, the music stops here and resumes elsewhere.

Paper understands this. So does soil.

Throwing a notebook into the recycling bin is a small rehearsal for a larger truth: nothing is meant to be hoarded forever. Not words. Not seasons. Not bodies. Nothing is wasted when it’s allowed to return.

This awareness doesn’t make me careless with my health. Quite the opposite. I take care of the instrument because it matters, not because it’s permanent. Stewardship replaces superstition. Vitality without denial.

There’s another layer to this practice that matters just as much.

When I begin my day with a creative act that contains no performance and no extraction, no ulterior motive and no hoped-for payoff, I set a precedent for everything that follows. It greases the pole. It primes the pump. It loosens the chaff from the grain.

The day inherits that ethic.

Work unfolds with less drag. Conversations move without strain. I can barely remember the last creative block I had to drag myself over, because I’m no longer beginning the day already in debt to an outcome.

Writing with gusto, passion, and honesty, then tossing the result away, is an antidote to a culture bunkered down in survival mode. A world where time is money, where you’re already late to a meeting you know will be boring and unnecessary, where every action is quietly auditioning for relevance.

Survival mode hoards.

Creative life circulates.

A creative life lets things—and people—go because it trusts continuity. It trusts that what matters will migrate outward into lived presence before the paper, and eventually the body, returns to earth.

I don’t save notebooks.

I become what they taught me.

And then I let them go.

Not a Warehouse Under Siege

I have learned something the long way around.

The teaching was never asceticism.

It was trust in circulation.

That sentence would have sounded irresponsible to me once. Maybe even dangerous. Because long before I ever crossed an ocean, long before I learned how little I could carry and still live well, something else had already been installed in the body.

Survival.

Not as a philosophy. As an inheritance.

A survivalist posture has been encoded into our species through uncountable hard winters, droughts, famines, wars, and devastations. It moved through family stories and unspoken grief. It passed from mother to fetus not through language, but through chemistry. Vigilance in the blood. Eat when you can. Keep what you find. Don’t trust tomorrow.

Babies buried before their first birthday will do that to a lineage.

So when I walk into homes now, I don’t see greed. I see history. Closets jammed with extra umbrellas. Coats that haven’t been worn in years. Children’s toys that belong to children who now have children of their own. Attics sealed shut, untouched for nearly a decade. Muffin tops that unbuckle belts the moment the door closes behind them.

None of this is failure. It is memory without a place to go.

For six years I’ve lived differently, not as an ideology, but as a consequence. I’ve moved through Europe with my belongings reduced to what I could physically carry onto a train or ride down a mountain on a bike. That kind of life strips language of its abstractions. You learn quickly what earns its weight.

Here’s what surprised me most.

Everywhere I lived, people were drowning in provisions.

And everything I actually needed had a way of showing up.

Not because I manifested it.

Because it was already there.

Often at the bottom of one of those overstuffed closets. On an empty afternoon. The internet down for a couple of hours. Hands doing honest work. Something long forgotten re-entering circulation.

I didn’t buy it. I freed it.

This is where an old story snapped into focus for me. Jesus didn’t arrive in Jerusalem on a horse he owned. He borrowed a donkey. He returned it. He didn’t stockpile the means of arrival. He had access.

Ownership says: I must secure the future.

Access says: the future is responsive.

We’ve misunderstood that teaching because we misunderstood heaven. We were trained to think of it as a place we go after we die, rather than a way of inhabiting life now once the calibration shifts. “Store up treasure in heaven” was never about delayed reward. It was about investing in what cannot rust because it is alive.

Language in the mouth.

Presence in the body.

Discernment in relationship.

A trained eye.

A steady hand.

A nervous system that can rest inside uncertainty.

Those things travel.

I’m not a minimalist. Minimalism is often just fear dressed in restraint. And I’m not a maximalist either. That’s appetite without discernment. What I’ve become, if anything, is a migratory accumulator. My life expands, but only in ways that remain portable. What I gather compounds rather than clutters.

Most people today live as if life were a warehouse under siege. Fortify. Stockpile. Seal the attic. Guard against loss at all costs. And in doing so, they quietly lose circulation, which is where life actually happens.

Trust in circulation doesn’t deny history. It completes it. It lets the survival instinct finally stand down. It teaches the body that winter no longer defines the calendar. That provision can arrive through relationship instead of hoarding. That safety can come from responsiveness rather than excess.

We didn’t become this way because we were foolish.

We became this way because we survived.

Now some of us are learning how to live.

And that requires a different kind of courage entirely.

If this piece resonates, becoming a paid subscriber is a simple way to keep this work in circulation.

Your support helps me continue writing these essays from lived experience rather than theory, and it keeps this space free from urgency, outrage, and noise. Think of it less as a transaction and more like putting something in the traveler’s pouch so the journey can continue.

If you’ve been nourished here, you’re welcome to help sustain the table.

Live Your Best Impossible Life

I have learned something the long way around.

A good life does not ask permission.

For the last several years, my life has looked, from the outside, irregular at best and reckless at worst. I have lived in places I was told I had no right to occupy. I have been removed, displaced, and locked out more times than I can count. Sometimes it came with polite smiles and paperwork. Once it came in the middle of the night, when I was pulled from my bed and beaten until I was left in the street, half naked and bleeding. I have slept in beauty and in precarity, sometimes within the same month.

And yet, when I tell the story honestly, something else emerges.

I had a lot of very good days.

I once lived alone in an abandoned stone house on a mountain in Tuscany. It had no running water, no electricity, and no assurances. What it did have was silence, forest light, and the slow discipline of making a place habitable with my own hands. I scavenged wood from a defunct cattle barn, cut chestnut trees from the forest, hauled a wood stove up the mountain with borrowed tools and the help of a friend’s tractor. At night, wild boar rutted through the leaves and roe deer cried out in the dark like something ancient remembering itself.

After five months, the predictable happened. The police came. The owner was angry. I was given two days to leave, then told I wouldn’t even have that. The lock would be changed.

That night I packed what mattered. I burned what I couldn’t carry and didn’t want discovered. I took my paintings off their stretchers and rolled them. At dawn, I rode down the mountain with my life in a duffle bag and my guitar on my back. I sold my bicycle for a hundred euros and caught the early bus to Florence, where I had arranged to meet a woman for one evening and nothing beyond it.

Three hours later, standing in the train station, my phone lit up.

It was a message from the owner. The angry one. The lawyer.

“I went to the little house today,” he wrote. “I saw what you did. I could hardly believe my eyes. You are a kind and beautiful man. What you did is unbelievable. Please come back. You can stay as long as you wish. I am so sorry. I just didn’t know.”

I returned after that single night in Florence. I bought my bike back. I rode up the mountain again. The next day he came with his sister and food from his mother’s kitchen, still warm. In Italy, that is not hospitality. That is adoption.

I exaggerate nothing. It happened exactly like that.

Years later, a painting I made in that stone house sold through a gallery in Chicago for $5,600. The frame was handmade from a wild chestnut tree I cut from that same forest. When I shipped the piece from Italy, I labeled it a “card table” and valued it at seventy-five euros because I didn’t yet have the right tax number to move art across borders.

It traveled under a temporary name.

Later, it stood in the light.

I am not telling you this to romanticize hardship or excuse systems that fail people. Violence is violence. Displacement wounds the body. Injustice is real. I’ve known all of that too well.

But there is another truth running beneath the dominant cultural story, and it’s one we’ve been trained not to see.

The lives that matter most rarely unfold inside clean lanes.

The apostle Paul didn’t wait for stable housing before writing letters that would shape civilizations. Esther didn’t save her people from the safety of the sidelines. These stories are not about virtue rewarded with comfort. They are about people placed improbably, operating without guarantees, whose depth was forged before their legitimacy was recognized.

Hollywood tells us a different myth. So does advertising. So does the trillion-dollar pornography industry and the insistence that a life only counts if it arrives wrapped in youth, money, and a retirement plan polished like a coffin.

Those are pacifiers.

The older stories say something riskier and far more useful:

Meaning precedes permission.

Depth precedes security.

Value often exists long before it is allowed to declare itself.

Living an “impossible” life doesn’t mean living irresponsibly. It means refusing to postpone aliveness until conditions look respectable. It means creating beauty inside constraint, telling the truth even when it has to travel under an alias, and trusting that what is real will eventually reveal itself.

Not on your timeline.

Not without cost.

But unmistakably.

If there is anything I have learned, it is this:

You are not here to wait until the world agrees with you before you begin.

You are here to live in such a way that, one day, the world has to revise its story.

That revision may come late.

It may come quietly.

But it comes.

Live your best impossible life.

Not because it’s easy.

But because it’s the only one that tells the truth.

Layered Time and Paintings as Thresholds

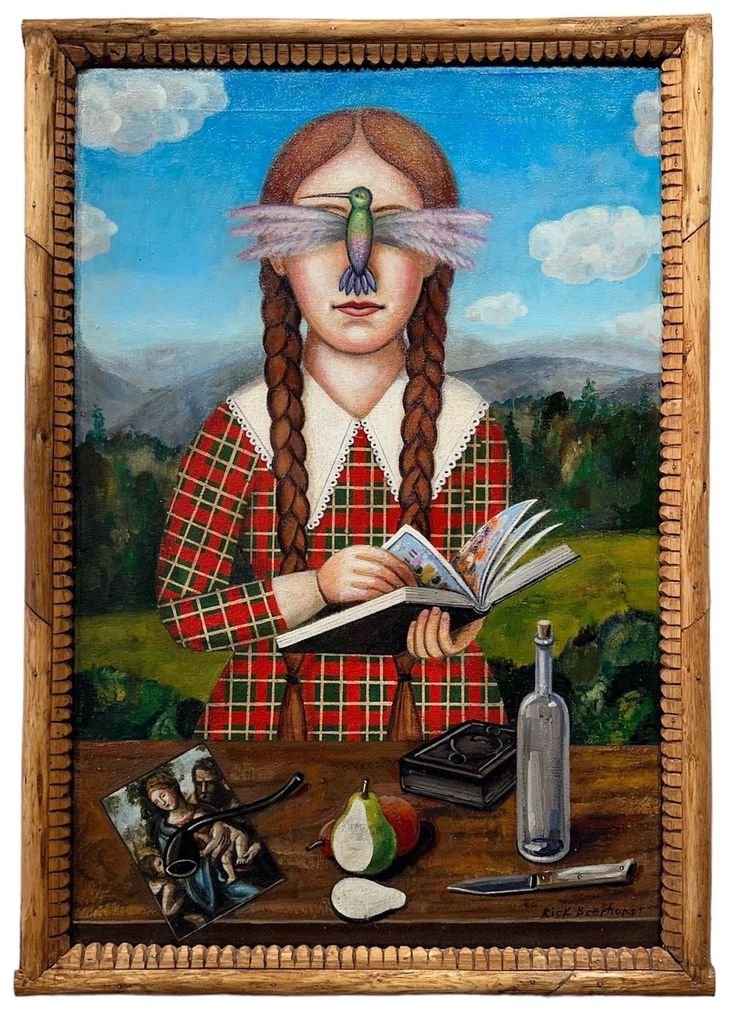

My Favorite Book, oil on linen, 30×30cm

This morning began the way many of my mornings do now.

Before the city fully woke.

Before language arrived with its errands and obligations.

A long meditation.

A slow walk through the body.

Attention oscillating between focus and openness.

Converging, then widening.

Center by center.

Until awareness no longer felt housed in me, but threaded through me.

Afterward, I noticed the familiar sensation.

As if something had been tuned.

Not revved up.

Quietly calibrated.

Like an engine idling so smoothly you almost forget what it’s capable of.

I looked up and saw the painting on my worktable.

A piece I’ve been developing slowly this past week.

Lovingly.

Without forcing it to resolve too soon.

And the question arrived without drama:

Do I actually understand what I’m making?

Not in terms of style or subject.

But in terms of function.

Because something has been happening to me lately when I stand in front of certain paintings. Not just my own. Others too. Museum rooms. Small galleries. Private homes.

I stay longer than expected.

Time doesn’t stop.

But it loosens.

And during that lingering, something subtle begins to occur.

A kind of interior re-alignment.

Old impressions float up without stories attached.

Memories without names.

Familiarity without origin.

Sometimes it feels like a forgotten language brushing the surface.

Not something I once learned, but something I once knew.

Words, I’ve come to realize, don’t belong to that moment.

Words belong to linear time.

They move forward.

Sentence by sentence.

Cause, effect, explanation.

But what happens in those moments of sustained looking belongs to something else entirely.

It belongs to layered time.

Layered time isn’t sequential.

It’s simultaneous.

Multiple registers of experience are active at once.

Body sensation.

Emotional tone.

Spatial awareness.

Memory without narrative.

A sense of meaning without conclusion.

Nothing is “next.”

Everything is already present, just at different depths.

At this point, the essay could easily explain itself.

But explanation would pull us back into linear time.

What follows doesn’t aim to clarify so much as to stay.

If you’d like to linger a little longer inside this question, the rest of the piece continues below for paid subscribers.

And the moment I try to explain what’s happening while it’s happening, the experience thins. Language pulls me back to the surface. Not because it’s wrong, but because it’s designed for reporting, not inhabiting.

This is where another realization has been quietly forming.

What if layered time corresponds to how our true mind actually works?

Not as something confined to the brain alone, but as a distributed intelligence.

A through-line of awareness running up the body and, at times, beyond it.

Thinking not only through thought, but through posture, sensation, resonance, and presence.

When attention settles into layered time, cognition stops feeling like analysis and starts feeling like listening.

The body participates.

The space around the body participates.

Awareness becomes less point-like and more atmospheric.

Deeply embodied.

And strangely unbounded.

This isn’t dissociation.

It’s integration.

And it makes me wonder whether certain paintings, when made and encountered under the right conditions, can function less like images and more like thresholds.

Not portals that promise escape.

But quiet relocations of attention.

Paintings that don’t demand interpretation.

Paintings that reward staying.

Perhaps this is why I’m increasingly drawn to restraint.

To ambiguity.

To images that don’t rush the viewer toward meaning.

Perhaps my work isn’t asking to be understood so much as inhabited.

When someone tells me, “I stayed longer than I expected,” I now hear it differently.

Not as a compliment.

But as a temporal confession.

Something in them found permission to surface without being interrogated.

And maybe that’s enough.

Maybe meaning doesn’t need to be delivered.

Maybe it only needs a place to arrive.

Paris, on a quiet Sunday, feels like a good place to let that question remain open.

If you’ve ever stayed longer than expected, I’d love to hear where that lingering took you

After the Auction Lights Go Out

Paris, late evening.

Last night I fell down one of those familiar corridors on YouTube. Art documentaries. Big names. Big rooms. Big numbers spoken with reverence. Auction houses. Dealers. Legends assembled like constellations.

For a while, it’s intoxicating. The scale. The certainty. The implication that this is what a “real” art life looks like.

And then, quietly, something else arrived.

A kind of exhaustion.

Not envy exactly. More like collapse.

Looking back over my own forty-year art life, it suddenly seemed small by those measures. Fragmented. Uneven. No towering auction results. No machinery humming behind my name. Just a long path of making, moving, leaving, returning, beginning again. Years of work carried forward more by devotion than momentum.

I sat with that feeling longer than I expected.

And then a different question surfaced. One that never appears in those films.

How happy were they, really?

How inhabitable was that life from the inside?

What gets edited out when success is framed only through scale, visibility, and spectacle?

The question didn’t arrive with accusation. It arrived gently, almost tenderly. As if asking to restore something human to a story that had grown too polished to breathe.

If someone were to bring a patient camera into my life, and a writer who knew how to listen rather than amplify, gather the work, the places, the seasons, the ruptures, the quiet mornings and the long stretches of uncertainty, it wouldn’t be a small story at all.

It would simply be a lived one.

A man staying with his work across decades. Learning how to remain intact. Learning how to make without disappearing into myth or machinery. Learning how to live a life that can actually be inhabited.

This morning, Paris was unchanged by my late-night reckoning. Light fell across the wall. A cup warmed my hands. Breath arrived without instruction. Nothing dramatic announced itself.

And that was the point.

I’m not waiting for my life to begin.

I’m not postponing myself until some future milestone arrives.

I’m already here.

Alive.

Aware.

Content in ways that don’t require explanation.

Whatever else may or may not come, this part matters. And it counts.

(Feel free to leave a note in the comments. I read them slowly.)

From Paris.

As always.

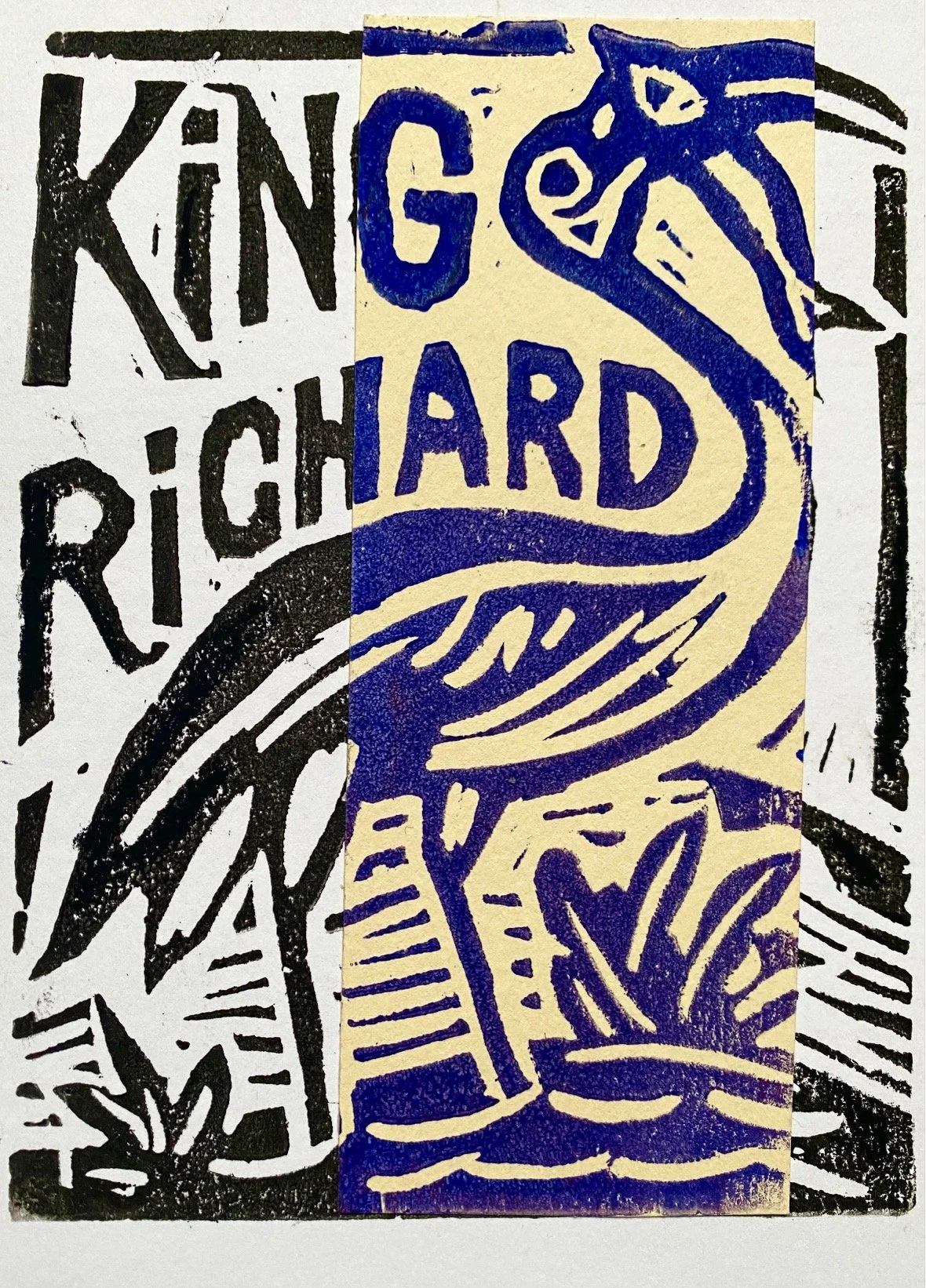

The Press and the King

Each morning I make my coffee with a French press.

It’s a simple ritual, almost forgettable, until one day it isn’t.

Hot water meets the grounds and nothing dramatic happens. There is color, aroma, potential. Then comes the waiting. The steeping. The patience. And finally the slow descent of the plunger. Pressure, applied evenly, without violence. What emerges is not chaos, but something rich, clear, and sustaining.

It struck me recently that life appears to be built on the same architecture.

There are moments when we are placed inside pressurized chambers. Not as punishment, not as evidence of failure, but as part of the brewing. The heat has already done its work. Time has already softened what needs softening. Pressure is simply the final stage that brings depth into form.

As a working artist for more than forty years, I know this chamber well. Living from the sale of one’s work means encountering seasons where the bank balance is low and the needs are not yet met. This kind of pressure can feel destabilizing, even hollowing, as if one is being carved from the inside while waiting for the next painting to find its home.

What I have learned, slowly and sometimes painfully, is that pressure cannot be relieved by force. There is no lever to pull, no acceleration that helps. The only viable posture is waiting without collapse. Holding one’s peace. Conjuring gratitude not as denial, but as alignment with a deeper truth.

And then, often without warning, someone appears. A collector. A patron. A beautiful human being who says yes. The painting is wrapped. The box is taped. Gratitude arrives not just as relief, but as recognition. This is how it has always worked.

When I say I wait upon the Lord, I do not mean an old man in the sky dispensing favors or thunderbolts. I mean something far more intimate and far more demanding.

The Lord, for me, is inner presence.

It is the stillness inside that remembers I have been here before. It is the inner King who governs my own kingdom, who never rushes to fix or explain. He leans back in repose, not from arrogance, but from certainty. He knows the outcome has already been determined, because he has lived the pattern enough times to trust it.

This kind of waiting is not passivity. It is command presence.

It is authority without theatrics.

It is faith grounded in experience rather than hope.

I see now that the pressure I feel in my life at present is not foreign. It is familiar, simply larger in scale. A deeper chamber. A richer brew. The same intelligence applies.

Hold.

Wait.

Do not crack the glass.

Pressure, when met with patience and dignity, does not crush.

It clarifies.

And when the moment comes, when the plunger reaches the bottom and the cup is filled, the result is always the same.

Something warm.

Something nourishing.

Something unmistakably good.

With love from Paris,

Rick

On Becoming My Own Savior

The Awakening

(Version française ci-dessous)

My Dear Reader,

When one of your children becomes hell-bent on ending their own life, it scrambles your mind and breaks your heart in ways no parenting book ever prepared you for. You think you’re helping—cooking their breakfast, straightening their room, trying to love them back into themselves—only to realize you may actually be making it worse. That the battle is theirs. That you cannot fight this one for them. You can comb their hair, but you cannot exorcise their demons.

Being a father to a boy who had become a runaway train headed for a collapsed trestle was a nightmare I couldn’t wake up from. My marriage melted into goo in the heat of those flames. And what I couldn’t see at the time—what I was blind to while living inside the storm—was the gift my son was giving me.

By creating that thunderstorm in our home, he dragged me into the mental breakdown I didn’t know I needed. The one that doubled as my spiritual awakening.

When I stood in the middle of everything I loved and watched it go up in flames like a barn in a lightning storm, I was also being carried—quietly, invisibly—on the wings of angels. Straight into the realization that heaven wasn’t a place you go when you die. It had been here the whole time, waiting like Dorothy’s red slippers. Waiting for me to click my heels and whisper:

There’s no place like home.

There’s no place like home.

My Get-Out-of-Dogma-Free card appeared in the form of a meditation app called Headspace. Twenty minutes each morning was enough to begin rewiring my entire way of being. It led me to the revelation that Jesus wasn’t a paschal lamb who died for my sins—he was my imagination. My inner scriptwriter. My own creative power wearing a story.

The woman caught in adultery, the loaves and fishes, the table-flipping rebel with a homemade whip—these stories were never history lessons. They were blueprints. They were reminders that heaven is something we build here, now, out of the raw materials of our own attention.

All I had to do was get still, close my eyes, and put my brain on a leash. Instead of letting it tear through back alleys knocking over trash cans, I learned to walk it to the dog park and feed it from my own hand.

My son’s thunderstorm knocked all the stuffing out of my Sunday School Jesus. What remained was the invitation—or the demand—to become my own savior.

Through a mix of daydreaming and inspired action, I began to remember why I slid into this complicated, radiant world in the first place.

And here in Paris, I continue remembering.

With love from Boulevard Voltaire,

Richard

Mon cher ami, ma chère amie,

Quand l’un de vos enfants devient farouchement déterminé à mettre fin à sa propre vie, cela vous retourne l’esprit et vous brise le cœur d’une manière qu’aucune Écriture sacrée, aucun manuel d’éducation ne vous avait préparé à vivre. Vous pensez aider — préparer son petit-déjeuner, ranger sa chambre, tenter de l’aimer assez fort pour qu’il revienne à lui-même — mais vous réalisez que vous aggravez peut-être les choses.

Que ce combat est le sien.

Que vous ne pouvez pas le mener à sa place.

Vous pouvez lui coiffer les cheveux, mais vous ne pouvez pas chasser ses démons.

Être le père d’un garçon devenu un train fou lancé vers un pont effondré était un cauchemar dont je ne pouvais pas me réveiller. Mon mariage a fondu comme de la cire sous la chaleur de ces flammes.

Et ce que je ne voyais pas alors — ce dont j’étais aveugle au cœur de la tempête — c’est que mon fils était en train de m’offrir un cadeau que je ne comprendrais que plus tard.

En déclenchant cet orage dans notre maison, il m’a entraîné dans la dépression nerveuse dont je n’avais pas conscience d’avoir besoin.

Celle qui deviendrait, sans que je le sache, mon éveil spirituel.

Quand je me suis retrouvé au milieu de tout ce que j’aimais, regardant ma vie partir en fumée comme une grange frappée par la foudre, j’étais aussi porté — doucement, invisiblement — sur les ailes des anges.

Tout droit vers la révélation que le paradis n’était pas un lieu lointain où l’on va après la mort. Il avait été là depuis le début, tout près, comme les souliers rouges de Dorothy, attendant que je clique les talons en murmurant :

« On n’est jamais mieux que chez soi.

On n’est jamais mieux que chez soi. »

Ma carte « Sortie de Dogme » est apparue sous la forme d’une application de méditation installée sur mon téléphone : Headspace.

Vingt minutes chaque matin ont suffi pour commencer à reconfigurer ma façon d’être au monde.

C’est là que j’ai découvert que Jésus n’était pas l’agneau pascal mort pour mes péchés — comme on me l’avait enseigné — mais mon imagination elle-même. Mon scénariste intérieur.

Mon pouvoir créateur enveloppé dans une histoire.

La femme surprise en adultère, les pains et les poissons surgis du néant, le renversement des tables des changeurs, le fouet fabriqué maison — rien de tout cela n’était un cours d’histoire.

C’étaient des plans.

Des modèles.

Des rappels que le paradis est quelque chose que l’on bâtit ici, maintenant, à partir de l’attention que l’on choisit d’offrir.

J’ai appris à devenir immobile, fermer les yeux, et mettre mon cerveau en laisse.

Au lieu de le laisser courir dans toutes les ruelles, renversant les poubelles en quête de nourriture, j’ai appris à le conduire au parc, où il pouvait profiter de la compagnie d’autres chiens et recevoir de ma main ses propres friandises.

L’orage provoqué par mon fils a vidé toute la ouate de mon Jésus d’École du dimanche.

Ce qui restait était l’invitation — ou peut-être l’exigence — de devenir mon propre sauveur.

À travers un mélange de rêverie et d’actions inspirées, j’ai commencé à me souvenir de la raison pour laquelle j’avais glissé hors du corps de ma mère pour entrer dans ce monde vaste, compliqué et pourtant lumineux.

Et ici, à Paris, je continue de m’en souvenir.

Avec chaleur, depuis le boulevard Voltaire,

Richard

When a Painting Turns Into a Witness

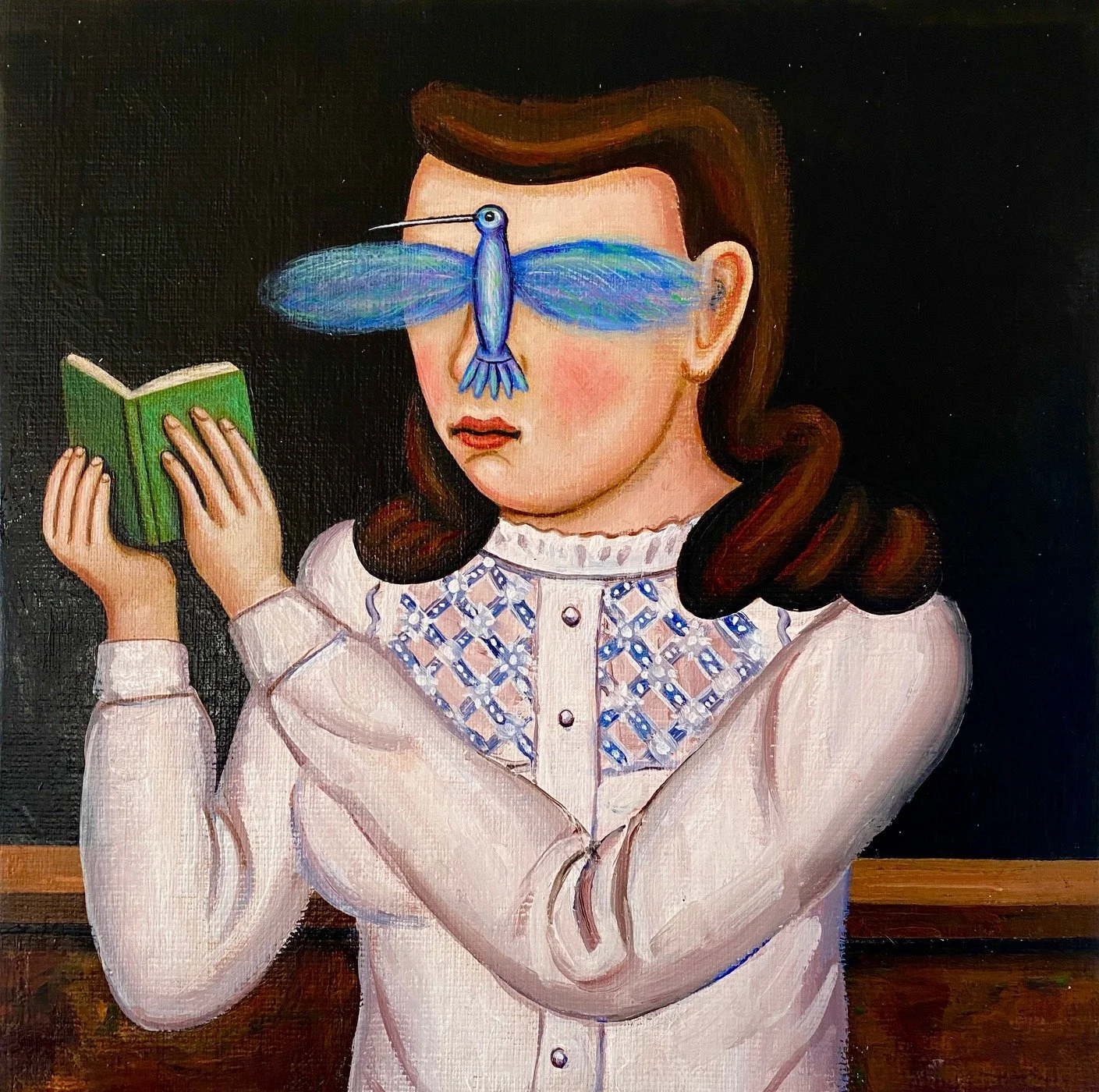

Two new self portraits that make more sense seen together.

Love Letter From Paris

Not to Stay There. But to Integrate It.

This week, I hung a painting in my studio.

That may sound ordinary, uneventful—but for me, it felt ceremonial. Something in me had been waiting for this moment—not to prove anything, but to witness it.

It’s a self-portrait I painted this past June, just as my exhibition

Beyond the Veil: Narrative Portraits by Rick Beerhorst

was coming down.

Not one painting sold.

Paris was bright and untroubled.

I didn’t yet sense the storm that was forming.

The portrait is of me—barefoot, seated, holding a book, a white deer resting calmly beside me. Painted in my apartment on Rue des Tournelles, before everything changed. Before the night of blood and eviction. Before I found myself alone on the street, holding only my dignity.

At the time, I didn’t realize what I was painting.

Only now do I understand:

I had painted a moment of stillness

just before the storm.

For months, I could not look at it. It lived silently in a corner, face-in, like a guest I could not yet face.

Not because it reminded me of what I had lost—

but because it reminded me of what I had not yet become.

But this week,

in my studio on Boulevard Voltaire,

I lifted it back onto the wall.

Not to stay there.

But to integrate it.

Because this is what I’m learning:

We don’t heal by erasing the past.

We heal by giving it a place in the present.

Not to glorify it.

Not to dwell there.

Simply to include it.

That painting wasn’t a symbol of pain.

It became a witness of continuity.

It reminded me that even before the disruption,

there had already been strength.

Even before the violation, there had already been truth.

Even before the eviction, there had already been a home—

one that no one could take from me.

Above it, I hung another self-portrait.

Painted recently,

but lived much earlier.

It remembers Tuscany.

My year in solitude.

My bronzed skin, shaved head, silent evenings with the hills.

My apprenticeship to stillness.

The first portrait whispers: You didn’t know yet.

The second replies: But you were already becoming.

That is the story today.

I don’t hang the paintings to reflect on what happened.

I hang them because of what I understand now.

My life didn’t break.

It revealed how unbreakable it had already become.

So I hung the painting.

Not to stay there.

But to integrate it.

—

Paris keeps teaching me:

Wisdom is not what you’ve been through.

Wisdom is what you’ve integrated.

Thank you for walking alongside me, even quietly.

More soon—

from Paris,

where some paintings speak before I do.

—Rick

In the Footsteps of Gertrude Stein

Our first Voltaire Salon 11-15-25

Last Saturday night, we had the joy of hosting our very first Voltaire Salon with ten wonderful guests. Two of our dear friends, Pascal and Bastian, have this rare gift: they genuinely love people and seem to know just about everyone. Naturally, we made them our salon ambassadors, inviting them to connect us with like-minded souls who’d be drawn to an evening like this.

So, what exactly is the Voltaire Salon? Imagine our home: it’s on the fifth floor of a 200-year-old stone building on Boulevard Voltaire, right in the heart of the 11th district of Paris. This is where I share a life and a living space with fellow artist and companion, Véronique Cauchefer. Our vision is to host a recurring gathering here, creating a nurturing community around our art practice and offering inspiration to everyone who walks through the door.

We’ve always been inspired by the legendary gatherings of Gertrude Stein and Alice B. Toklas in their Paris apartment in the 1920s. Those salons were the cradle of modern art and literature. It’s where Matisse first encountered Picasso, where Hemingway was encouraged by Gertrude to step beyond journalism and truly find his voice as a novelist. These gatherings brought together artists, writers, and thinkers who might never have crossed paths otherwise — and from that alchemy, whole movements were born.

By weaving in this bit of history, we’re not just hosting a gathering — we’re tapping into a lineage of creative community that has thrived for generations. And in doing so, we invite our guests to become part of that ongoing story.

And of course, if you find yourself circling a piece or considering a first purchase, just send me a message on Instagram @richardbeerhorst. I’m always happy to guide you.

Stand and Deliver / Tiens bon et donne la vie

The night the midwife didn’t come became the night I was born too — not as a child, but as a man who learned to stand and deliver.

November 12th, Saturday — Samedi 12 novembre

Dove when she visited me in Tuscany on Mt Amiata

The power of intention is simply everything. And now that I’m here—the smell of a buttery warm croissant, the seagulls over the Seine, the buildings that have stood here shoulder to shoulder for centuries—it all feels not only perfect but better than anything else I’ve ever known.

As I sit here now, everything feels steady, luminous. But I know that calm only because I’ve met its opposite. Twenty-three years ago, in a small house in Grand Rapids, I was tested in a way that changed me forever.

It was 3:30 in the morning when it became clear the midwife was not coming and we would have to deliver this baby on our own. Those first moments of realization were sheer terror, quickly followed by the quiet command to act.

We were living in our first house then, an old working-class Victorian wood-frame place tucked inside a tough neighborhood—welfare mothers, grandmothers in at-home hospital beds, street gangs like the Cherry Boys and the Logan Doggers. Prostitution at one end, a big church parking lot at the other, where one, two, sometimes three police cars sat idling in the dark—probably chatting, smoking, or filling out their endless forms while the rest of us learned to sleep through the sirens and random gunshots.

And there we were, in that same neighborhood, ready to deliver our fourth child. Her water broke at 3:33 a.m. I called our midwife, Yolanda, who said, “I’m putting on a pot of tea and will be there soon.” But soon was not soon enough, because that’s when my wife screamed, “The baby’s coming now!”

She was standing, leaning against the porcelain pedestal sink, caught in the rhythm of those hard contractions. The baby wouldn’t come down. I could feel something wasn’t right. Doing what I had seen Yolanda do with our other births, I slipped my hand inside her with my first two fingers extended until I could reach under the cord—wrapped not once but twice around the baby’s neck.

It felt just like an old-fashioned telephone cord. I slipped it off, and in that instant she was free. The very next contraction came like thunder, and Dove was suddenly in my hands—warm, slippery, and full of wiggling life.

The room went silent for a beat, then flooded with sound: her cry, our laughter, our cheeks wet with tears, the rush of water still running from the tap. Relief and awe mixed into something electric. There was blood on my arms, steam on the mirror, the first hint of morning pressing at the window.

I remember grabbing a pie spatula from the kitchen to clean the mess from the yellow pine floor of our bathroom. The smell of birth, metal, and soap all tangled in the air. And then, as if on cue, Yolanda finally arrived—just in time to oversee the passing of the placenta and snip the cord.

That night changed everything. What looked like disaster had become miracle. The fear that had gripped my chest turned to stillness, and something ancient took over—something that knew exactly what to do.

From that moment forward I carried the truth that was born with her: when it seems like the worst thing possible is happening, that’s the moment you stand and deliver. Every collapse carries a secret instruction; every terror conceals a hidden grace.

When I look back now, I see that night not only as Dove’s birth but as mine—the birth of the indestructible version of myself, the one who knows that even in the darkest hour there is always a way through, always the possibility of miracle.

Written from Paris, twenty-three years later.

...always the possibility of miracle.

*Written from Paris, twenty-three years later.*

— ✦ —

Le pouvoir de l’intention, c’est tout. Et maintenant que je suis ici — l’odeur d’un croissant chaud et beurré, les mouettes au-dessus de la Seine, les immeubles serrés les uns contre les autres depuis des siècles — tout paraît non seulement parfait, mais encore meilleur que tout ce que j’ai connu.

Assis ici, tout semble paisible, lumineux. Mais je connais cette paix parce que j’en ai déjà rencontré l’opposé. Il y a vingt-trois ans, dans une petite maison de Grand Rapids, j’ai été mis à l’épreuve d’une manière qui m’a changé pour toujours.

Il était trois heures et demie du matin lorsque j’ai compris que la sage-femme ne viendrait pas et que nous allions devoir faire naître ce bébé seuls. Les premières secondes furent de la pure terreur, vite suivies par une voix intérieure qui disait simplement : agis.

Nous vivions alors dans notre première maison, une vieille demeure victorienne en bois, au cœur d’un quartier difficile : mères au chômage, grands-mères alitées dans leurs lits d’hôpital à domicile, gangs de rue comme les Cherry Boys et les Logan Doggers. De la prostitution à une extrémité, et à l’autre un grand parking d’église où une, deux, parfois trois voitures de police restaient au ralenti dans l’obscurité — sans doute en train de discuter, de fumer ou de remplir leurs interminables formulaires — pendant que nous apprenions à dormir malgré les sirènes et les coups de feu sporadiques.

Et c’est là, dans ce même quartier, que nous nous apprêtions à accueillir notre quatrième enfant. Sa poche des eaux s’est rompue à 3 h 33. J’ai appelé notre sage-femme, Yolanda, qui m’a dit : « Je mets de l’eau à bouillir pour le thé et j’arrive bientôt. » Mais bientôt n’a pas été assez tôt, car à ce moment-là ma femme a crié : « Le bébé arrive maintenant ! »

Elle était debout, appuyée contre le lavabo en porcelaine, secouée par le rythme puissant des contractions. Le bébé ne descendait pas. Je sentais que quelque chose n’allait pas. Faisant ce que j’avais vu Yolanda faire lors des autres naissances, j’ai glissé ma main à l’intérieur, les deux premiers doigts tendus, jusqu’à sentir le cordon — enroulé non pas une, mais deux fois autour du cou du bébé.

C’était comme un vieux cordon de téléphone. Je l’ai délicatement fait passer par-dessus, et à cet instant, elle était libre. La contraction suivante est arrivée comme un coup de tonnerre, et Dove était soudain dans mes mains — tiède, glissante, pleine de vie.

La pièce est restée silencieuse un bref instant, puis tout s’est empli de sons : ses pleurs, nos rires, nos joues mouillées de larmes, l’eau qui coulait toujours du robinet. Le soulagement et la joie se mêlaient en une énergie presque électrique. J’avais du sang sur les bras, de la buée sur le miroir, et la première lueur du matin glissait à travers la fenêtre.

Je me souviens avoir attrapé une spatule à tarte dans la cuisine pour nettoyer le sol en pin jaune de la salle de bain. L’odeur de naissance, de métal et de savon flottait dans l’air. Et puis, comme par miracle, Yolanda est enfin arrivée — juste à temps pour veiller à la délivrance du placenta et couper le cordon.

Cette nuit-là a tout changé. Ce qui ressemblait à un désastre s’est transformé en miracle. La peur qui m’écrasait la poitrine s’est changée en calme, et quelque chose d’ancien a pris le relais — quelque chose qui savait exactement quoi faire.

Depuis ce moment, je porte en moi la vérité née avec elle : quand tout semble s’effondrer, c’est justement l’instant où il faut tenir bon et donner la vie. Chaque effondrement contient une instruction secrète ; chaque terreur cache une grâce dissimulée.

Quand je regarde en arrière aujourd’hui, je vois cette nuit non seulement comme la naissance de Dove, mais aussi comme la mienne — la naissance de cette version indestructible de moi-même, celle qui sait que, même dans la plus sombre des heures, il y a toujours un passage, toujours la possibilité du miracle.

Écrit à Paris, vingt-trois ans plus tard.

What the Mountain Taught Me About Meaning

After months of living alone on Mount Amiata in the Tuscan wilderness, I left with only what would fit in a duffel bag.

No Wi-Fi, no convenience — water carried in from a spring, firewood cut by hand, and silence that chiseled away everything non-essential. That mountain reminded me that meaning isn’t streamed; it’s carved, hauled, and earned by hand.

My paintings come from that place — a cantilever over the digital flood. They carry the smoke of that stone house, the breath of the forest, the proof that the real still matters. Every brushstroke is a way back home.

To live now in Paris, in this luminous apartment on Boulevard Voltaire, feels like the plush lap of luxury. I see that our lives need the deep cut of contrast in order to rise into the sublime.

I left the forest, but it remains inside me. That re-wilding led me back to the boy of thirteen — sitting in the woods with a pencil and a sketchbook — rediscovering the freedom that begins where the street ends and the wild begins.

Ce que la montagne m’a appris sur le sens

Après des mois passés seul sur le mont Amiata, dans la nature sauvage de Toscane, je suis parti avec seulement ce qui tenait dans un sac de voyage.

Pas de Wi-Fi, pas de confort — l’eau puisée à la source, le bois coupé à la main, et le silence qui a façonné en moi tout ce qui devait disparaître. Cette montagne m’a rappelé que le sens ne se diffuse pas ; il se sculpte, se porte, et s’obtient à la force des mains.

Mes peintures viennent de cet endroit — comme une console suspendue au-dessus du déluge numérique.

Elles portent la fumée de cette maison de pierre, le souffle de la forêt, la preuve que le réel compte encore.

Chaque coup de pinceau est un chemin de retour vers la maison.

Vivre aujourd’hui à Paris, dans cet appartement lumineux du boulevard Voltaire, c’est ressentir le velours du luxe.

Je comprends que nos vies ont besoin de la profonde entaille du contraste pour s’élever vers le sublime.

J’ai quitté la forêt, mais elle demeure en moi.

Ce retour au sauvage m’a ramené vers le garçon de treize ans — assis dans les bois avec un crayon et un carnet de croquis — retrouvant la liberté qui commence là où la rue s’arrête et où le sauvage reprend ses droits.

Cette lettre est aussi une invitation : à retrouver votre propre parcelle de nature sauvage, quelle qu’en soit la forme.

Un lieu où le silence parle, où le réel revient, et où la vie retrouve le goût du travail des mains.

No More Playing Small

Last night found me wiping away tears as the credits rolled on the new Springsteen biopic Deliver Me From Nowhere.

It’s the story of an artist using poetry and rock & roll to pull himself out of the haunted house he grew up in. We were given glimpses of Springsteen pouring out his heart on stage, drenched in sweat before a fast-growing audience during his breakout years.

But the part that really undid me — the one that took forty-five years to be told — was the story behind the curtain: a young man nearly overcome by the same darkness that had haunted his father. This was Bruce not yet “The Boss,” a man who almost didn’t make it out alive.

We saw how his manager and a diner-waitress girlfriend anchored him back to solid ground. They gave him both the truth and the love that kept him from disappearing into the black hole of his own success.

The fact that Bruce Springsteen didn’t become just another post-star casualty — crashing into an early death — had everything to do with the people who gave him something real to hold on to. Real friendship. Real truth. The kind that gives a man the courage to face his ghosts and stop running.

He had to choose not just to survive, but to rise up and play the role of a man honest about who he was and where he came from.

This hit me hard last night because in the months since the violent assault this summer, I’ve found myself teetering on the edge of my own darkness again.

My tears came from the resonance chord tugging at my heartstrings — a reminder that the era of playing small is over. There’s no more hiding behind the quiet.

It’s time to stand in the full heat of the stage lights, unflinching.

—Rick

Paris, October 2025

If you’re done playing small, this is your invitation to step into the fire with me.

Book your consultation →

This is not nostalgia. It’s ignition.

Over the past several days, I’ve been pulling my images, my work, my story out of digital corners — Facebook, Flickr, Instagram — and bringing them home to Pinterest.

Pinterest has become my loom. Each image a thread. Each thread a part of a story that has been waiting to be seen whole.

As I gather them, something stirs.

A sleeping part of me sits up.

This is what it means to re-member:

to wake from the enchanted sleep of forgetfulness

and feel the pulse of our own myth again.

This isn’t just my awakening.

My re-membering is yours, too.

It belongs to all of us who have forgotten our own magnificence,

who have allowed the misty amnesia of time to dull our edges.

This letter is the kiss —

the moment the spell breaks

and the body of your story wakes up again.

Not long ago, teenagers spent their afternoons building treehouses or Lego starships.

Now, many of them build worlds in cyberspace on borrowed laptops — transforming scattered bits of code and vision into new abundance.

That image has been echoing in me lately. Because in my own way, I’m doing something similar right now:

spreading out the puzzle pieces of my pilgrimage on Pinterest like a map on a coffee table.

And as the pieces come together, so does the narrative arc of my life.

Once the story is visible, the future stops hovering at the horizon.

It starts humming like a finely tuned engine, ready to run.

If this sparked off something that is awakening in you perhaps we should work together. If that sound good go over hear

The Dusty Lego Bin

I’m now standing in a place where I have a real audience reading my work — and some of these people are rather famous, important, accomplished.

Well, they’re all important, of course.

These days I am living right now are not quite the payout times. This is not when the checks get cashed, the reservations are made, the clothes are purchased, and the rewards of a long creative pilgrimage finally begin to unfold — but it’s damn close.

I find myself in an exceedingly powerful position because these are the days of the creative. The ones who excelled in school by following rules, doing their homework, and extra credit — they are becoming the dinosaurs, stuck in the tar pits of fear, worrying about AI taking over. They lament smartphone addiction and the fact that kids don’t build treehouses anymore, missing that these kids are busy designing apps with AI, becoming the next multimillionaires, while the plastic bins of Legos gather dust.

The future doesn’t belong to those who cling to what was.

It belongs to the ones who can imagine something that doesn’t exist yet — and have the nerve to build it.

That’s what artists have always done.

We don’t wait for permission.

We don’t wait for the map.

We make the map.

I’ve learned how to die and be reborn while still alive. I’ve lived multiple lives in this same body. I am a ninja pivoter — beyond resilient, unsinkable, a shape-shifter. I will thrive in this new world because I was made for it.

Legos weren't my generation. I can still hear the sound of my son raking through his plastic bin looking for that right piece. I loved knowing he was doing something that connected his hands with his brain. That’s a good memory but I’ve lived enough lives to know the world is built and rebuilt by those willing to imagine something new.

Love Letters From Paris: Morning Pages

Artist and writer Richard Beerhorst shares his morning writing ritual from Paris, inspired by Julia Cameron and Neale Donald Walsch. A meditation on creativity, journaling, and the quiet holiness that begins each day with a Bic pen and a blank page.

When my Bic pen touches the paper in the morning, I have the sense of turning something on. It feels like a signal—an invisible bell summoning my unseen companions to come closer and lean in. This is my holy of holies, my personal sacred space. The blank white page before me is my life, waiting to be dreamed into existence.

I can’t quite remember when I began doing this regularly, but it must be over twenty years now. I first encountered the idea in The Artist’s Way by Julia Cameron, a book that speaks to the basic properties of creativity and how to protect this fragile, essential quality in one’s life. The world we currently occupy doesn’t exactly encourage the “artist’s way,” to say the least. In her groundbreaking book, Julia encourages the reader to write three pages of anything first thing in the morning.

This does at least two very important things. First, it’s a simple way of declaring, at the start of the day, that you are first and foremost a creator. Second, it’s a way of clearing the pipes—of letting the inner waters run free. When I was a boy growing up in the suburbs, we learned to let the garden hose run for a while before taking a drink. The first rush of water was warm, tasting of rubber. But if you waited, the flow soon turned cool and fresh. Writing morning pages is like that: letting the water run awhile.

It doesn’t matter so much what you write, only that you write. If you get stuck at the beginning, you can simply repeat a few sentences over and over. Eventually, the words, the sentences, and the ideas will begin to come.

For me, I like to write down my visions and hopes for the future as if they’ve already manifested. This enriches my imagination and draws my desired life into form. Sometimes I let my future self step through—offering words of wisdom and gentle encouragement from a higher mind. There are even mornings when my future self will ask what I would tell the version of me who was slugging it out ten years ago.

Another book that has shaped my morning writing is Conversations with God by Neale Donald Walsch. In it, Walsch describes a time when he was lost and discouraged. He began writing a letter to God, filled with complaints and questions, and was astonished to find words answering him—clear, loving, and wiser than his own thoughts. That spontaneous exchange became a dialogue with divine intelligence, eventually published in three books that have helped millions move beyond the stale image of an old man in the sky and toward a living, breathing relationship with the sacred.

Each morning I sit down in the dark, pre-dawn—it feels like the earth before God created the animals and the first pair of humans, or perhaps the hour before the Big Bang itself.

The pen meets the page, and something unseen stirs.

Paris listens.

My hand moves.

And the day, once again, becomes holy.

Explore more:

– Letters from Paris Archive

– About Richard Beerhorst

– Recent Paintings

Letter from Paris: The Bear in Exile

My dear,

This afternoon I write to you with the steady hum of traffic rising from five floors below on Boulevard Voltaire. On the table before me rests a cast-iron bear I unearthed from the back of Vero’s closet, its weight startling me like a relic that had been waiting.

My name, Beerhorst—“bear’s forest”—has always carried its own myth. The bear alone in his cave, breathing through the long winter, hidden yet alive. I feel the truth of that image in my bones now.

I came to Paris from Mallorca in the spring with hope burning quietly in my chest

A Flame Circle card ready to be written to a new subscriber

My dear,

This afternoon I write to you with the steady hum of traffic rising from five floors below on Boulevard Voltaire. On the table before me rests a cast-iron bear I unearthed from the back of Vero’s closet, its weight startling me like a relic that had been waiting.

My name, Beerhorst—“bear’s forest”—has always carried its own myth. The bear alone in his cave, breathing through the long winter, hidden yet alive. I feel the truth of that image in my bones now.

I came to Paris from Mallorca in the spring with hope burning quietly in my chest, ready for my second solo exhibition—this time with the El Habibi Galerie. But the opening passed without a single sale. Month after month my account drained while the paintings leaned against walls in silence, like mute companions.

Then came the night of rupture—dragged into the street half-naked and bloodied, stripped of safety and certainty. Since then I have slept on a friend’s couch, my small thirty-by-thirty canvases stacked in the corner of her storage room, an orchard of fruit still waiting for its harvest.

And yet, even in this exile, myth comes close. I think of David—anointed but driven into caves, hunted by Saul, kept alive by the wilderness. His story whispers that I, too, am not only displaced but prepared. That exile is not the end but the apprenticeship of kingship. That the cave is not only a refuge but a forge.

This is what myth does—it presses depth into our days when the surface would otherwise swallow us. It tells us the bear is not only an animal but a mirror, the bloodied man in the street not only broken but becoming. In a world dazzled by surfaces, myth reminds us of the subterranean currents shaping our lives. It turns our ache into an anvil, our wandering into initiation.

Even here, especially here, I trust I am still being shaped for more than I can yet imagine.

Yours,

Rick

Check out the Thirty by Thirty series — my alchemical passage from blood bath to artistic rebirth.

Letters From Paris: On Self Portraits

Dear friends,

I have made countless self-portraits over the years—drawings, block prints, paintings. In this, I follow a lineage I admire deeply: Rembrandt, Van Gogh, Frida Kahlo, and Howard Finster. Each of them stood before the mirror and took a long, unflinching look at themselves. That takes courage.

Self Portraits, 156 × 156 cm, 2021-23

Joe Dispenza often reminds us that where we put our attention is where we send our power. If this is true, perhaps these artists were not only observing themselves, but empowering themselves in the very act of painting their own image.

I know this has been true for me. When I face the mirror, I ask: Am I still on track? Am I following the arc of my own story, or have I drifted into old programs from my youth?

This unblinking gaze was what enabled Frida to alchemize her relentless pain into art; what drew Rembrandt deeper into the magical chiaroscuro of his shadows; what kept Vincent working in obscurity, ignored by the art world of his time. It even lifted Howard from being a dirt-poor Baptist preacher to standing on the stage of The David Letterman Show.

I’m always a little surprised when someone purchases one of my self-portraits. They feel so personal—more like a journal entry than a public statement. But perhaps that is their charm. They are raw, terrifyingly personal, and therefore alive in a way other pieces never can be.

Maybe that’s why people choose to live with them—because in the end, the courage to see oneself clearly is something we all long for.

If this letter resonated, you can stand closer to the work through the Flame Circle